By the time the speech was over, so was the campaign, though the senator wouldn’t be sure of it until he saw it in his wife’s eyes. At that moment, he knew that the fallout from this evening would be swift and brutal. The once-grand ballroom of the Philadelphia banquet hall, which had earlier buzzed with the energy of 500 influential journalists and writers, now lay empty, a testament to the disastrous turn of events.

La Follette had spent weeks preparing for this moment, crafting words he believed would solidify his position as the frontrunner for the presidency. But as he spoke, he felt the energy in the room shift, his usually powerful and inspiring words falling flat against an increasingly restless audience.

the more he spoke, the more the crowd dwindled, their chairs scraping against the polished floor as they made their exit. Even La Follette’s friend and ally, Congressman Henry Cooper, couldn’t hide his concern, whispering to La Follette’s secretary, “This is terrible—he is making a damned fool of himself.”

In the days that followed, newspapers across the country ran scathing headlines, condemning La Follette’s performance. His once-loyal supporters began to distance themselves, their attention turning towards the rising star of Theodore Roosevelt. Retreating to his hotel room, La Follette sat with his head in his hands, as Belle tried to console him, her comforting presence unable to ease the sting of the disastrous evening.

The next move was his and his alone to make. A monumental decision that would shape the course of his campaign and legacy.

PROGRESSIVES IN PROGRESS

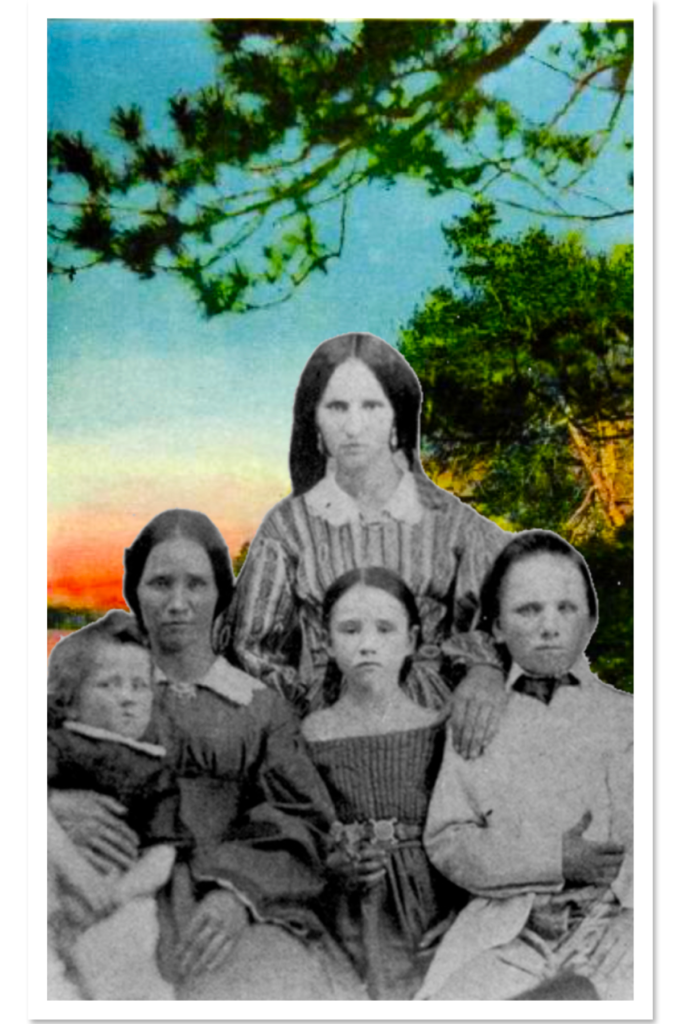

Robert La Follette was used to the pressure, as his life was shaped by tragedy and resilience from an early age. He never knew his father, who died when he was just eight months old. At the age of six, his mother remarried, introducing a stepfather whose influence would help mold young La Follette’s character and ambitions.

As La Follette navigated the challenges of his youth, he found solace and inspiration in the unwavering support of his beloved wife, Belle Case La Follette. The couple had met during their time at the University of Wisconsin, where Belle’s keen intellect and passionate advocacy for women’s rights had caught La Follette’s eye. Their partnership, built on a foundation of mutual respect and shared ideals, would prove to be a driving force behind La Follette’s political career and the progressive movement as a whole.

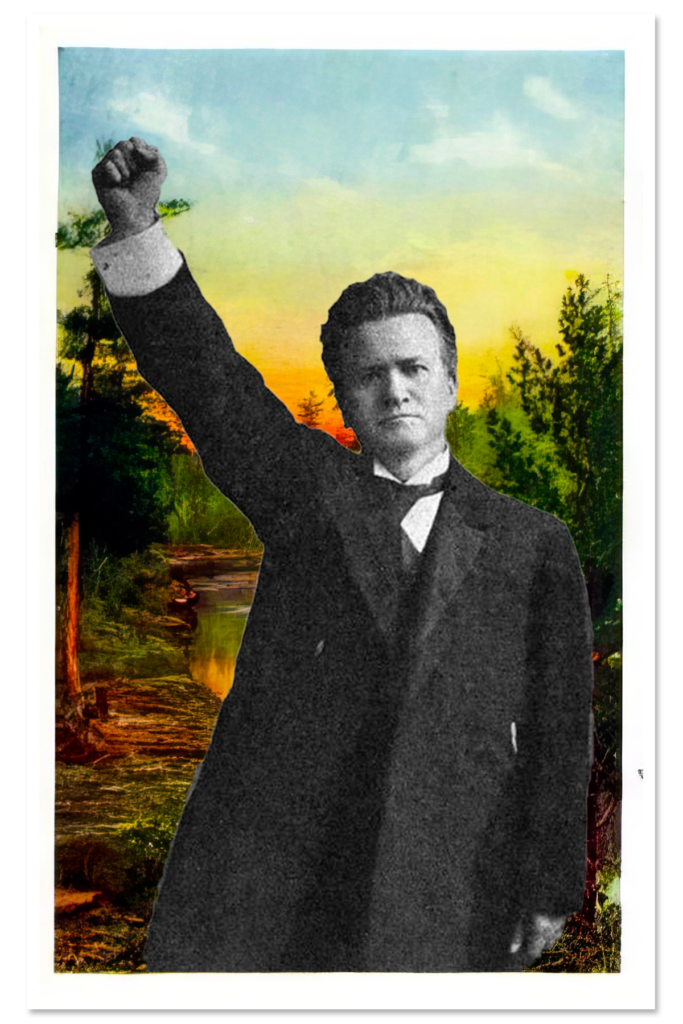

Together, the La Follettes honed their skills in oratory and debate, pouring their hearts into every recitation and speech. La Follette’s crowning achievement came with his victory in the Inter-State Oratorical Contest, where his electrifying rendition of “Iago” left the audience spellbound. Belle, too, excelled in these arenas, her passionate arguments for women’s suffrage and social justice earning her a reputation as a formidable advocate in her own right.

As La Follette embarked on his early foray into politics, taking on the role of Dane County District Attorney, Belle remained a constant source of support and guidance. Her keen political instincts and unwavering commitment to progressive ideals helped to shape La Follette’s approach to public service, instilling in him a deep sense of duty to challenge the status quo and fight for the common good.

La Follette quickly earned a reputation as a fearless prosecutor, taking on offenders from all walks of life with equal fervor. The young couple’s unwavering commitment to justice and their willingness to stand up to entrenched interests foreshadowed the principled stance that would define their political careers.

As La Follette’s star began to rise, Belle’s influence and contributions to the progressive cause only grew stronger. Her tireless work as a suffragist, her groundbreaking role as the first woman to graduate from the University of Wisconsin Law School, and her later position as co-editor of La Follette’s Magazine all served to amplify and extend the reach of the progressive message.

Through their shared passion, unshakable bond, and unwavering dedication to reform, Robert and Belle La Follette emerged as a true power couple of the progressive era, setting the stage for a lifetime of political and social activism that would leave an indelible mark on American history.

A VOICE FOR REFORM, A BODY POLITIQUE

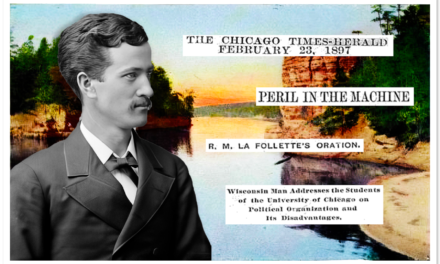

At 29, La Follette burst onto the national stage, winning a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. His arrival in Washington marked the beginning of a new era, as the young congressman wasted no time in challenging the entrenched power structures within the Republican Party. La Follette’s refusal to toe the party line and his insistence on speaking truth to power earned him a reputation as a maverick and an insurgent, a badge he would wear with pride throughout his career.

But the path to progress was not without its obstacles. In 1890, La Follette’s bid for re-election was derailed by the Bennett Law, a controversial piece of legislation that ignited a firestorm of opposition among Wisconsin’s immigrant communities. Though La Follette had not been directly involved in the law’s passage, he found himself swept away by the tide of discontent, his political future suddenly uncertain.

Undeterred, La Follette returned to Wisconsin, his resolve to fight corruption within the Republican Party only strengthened by his setback. He understood that true reform could only be achieved by taking on the entrenched interests that had long dominated the political landscape. With a steely determination and a fire in his belly, La Follette set his sights on the governor’s mansion, knowing that the road ahead would be long and arduous, but that the cause was just and the need for change, urgent.

THE WISCONSIN IDEAL

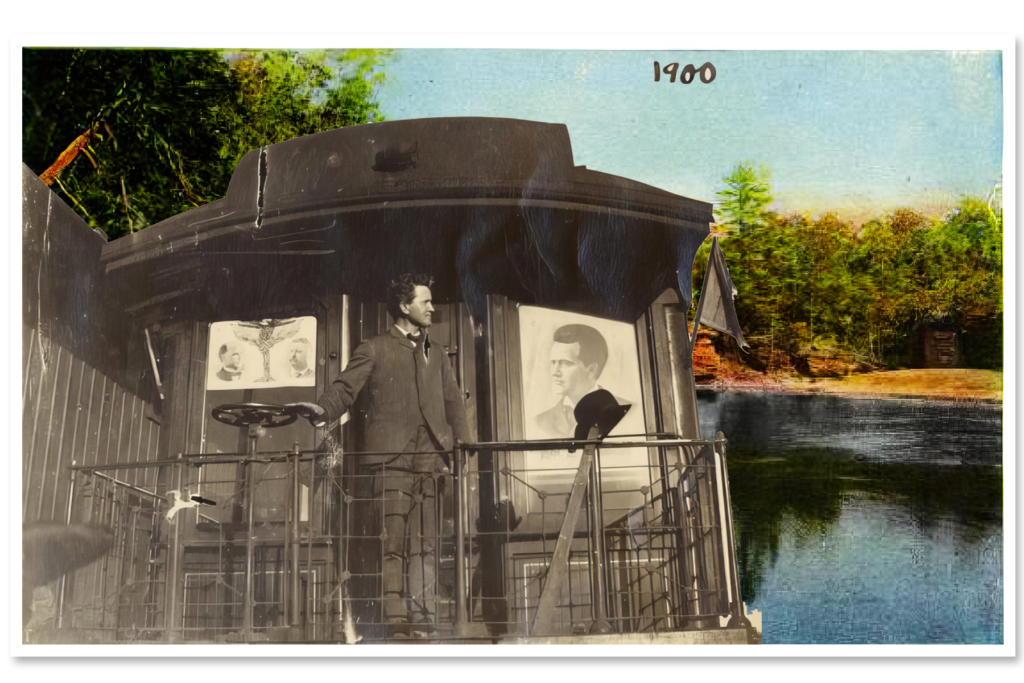

The dawn of the 20th century brought with it a new chapter in La Follette’s political journey. In 1900, he mounted a successful campaign for governor, crisscrossing the state and delivering impassioned speeches to packed houses. With his wife Belle by his side, La Follette’s message of reform and progress resonated with voters, who saw in him a champion for the common man.

As governor, La Follette wasted no time in implementing his vision for a more transparent and accountable government. He championed the Wisconsin Idea, a philosophy that emphasized the importance of collaboration between the state’s universities and its government. Working closely with Charles Van Hise, the President of the University of Wisconsin, and a team of brilliant faculty members, La Follette laid the groundwork for a new era of progressive reform.

Central to La Follette’s agenda was the direct primary system, a bold initiative that sought to wrest control of the political process from the smoke-filled backrooms of the party bosses and place it firmly in the hands of the people. Despite fierce opposition from entrenched interests, La Follette’s determination and the tireless efforts of Belle and their allies carried the day, forever altering the landscape of Wisconsin politics

TAKING IT TO THE (SENATE) FLOOR

In 1906, La Follette took his fight for reform to the halls of the U.S. Senate. From the moment he arrived in Washington, he made his presence felt, quickly establishing himself as a leading voice for progressive change. His clashes with the conservative Republican leadership and President Taft became the stuff of legend, as La Follette refused to back down in the face of fierce opposition.

Recognizing the need for a more organized and cohesive progressive movement, La Follette founded the National Progressive Republican League. This groundbreaking organization served as a rallying point for like-minded reformers, providing a platform for the exchange of ideas and the coordination of political action. As La Follette’s national profile grew, so too did speculation about his potential as a presidential candidate.

Behind the scenes, Belle La Follette played a crucial role in her husband’s political ascent. Through her work on La Follette’s Magazine, she helped to spread the progressive message far and wide, reaching countless readers with her incisive analysis and impassioned calls for reform. Together, the La Follettes formed a formidable partnership, united in their commitment to building a more just and equitable America.

THE CRUCIAL MOMENT

As the 1912 presidential campaign loomed on the horizon, tensions between La Follette and former president Theodore Roosevelt began to simmer. Both men saw themselves as the rightful heir to the progressive mantle, and their competing visions for the future of the movement threatened to fracture the delicate coalition that La Follette had worked so hard to build.

Undaunted, La Follette threw himself into the race, crisscrossing the country and delivering impassioned speeches to packed houses. But the strain of the campaign began to take its toll, both physically and mentally. Long days on the trail and endless rounds of speeches left La Follette exhausted and frayed, his once-sharp oratory beginning to falter.

It was in this context that La Follette arrived in Philadelphia for a fateful campaign speech. Taking the stage before a packed house, he poured his heart into his words, but something was off. The energy in the room felt different, the audience restless and unresponsive. As La Follette pushed on, his voice growing hoarse and his gestures increasingly erratic, a sense of unease began to ripple through the crowd.

Belle watched from the wings as he struggled to connect with his audience. She knew, deep down, that this moment could be the turning point of the campaign, the instant that would make or break La Follette’s presidential ambitions.

As La Follette left the stage, his shoulders slumped and his eyes downcast, Belle was there to meet him. Robert said nothing as they left the banquet hall. the time for talking was done, now he had to think. The future of the progressive movement hung in the balance.

THINGS GET WORSE, PROGRESSIVELY

The 1912 Republican Convention in Chicago was a crucible of discord, as the bitter nomination battle between Taft and Roosevelt threatened to tear the party asunder. La Follette, ever the principled outsider, found himself caught in the crosshairs of the warring factions. Despite immense pressure from his allies to support Roosevelt against Taft, La Follette remained steadfast in his refusal to compromise his ideals. And not for the man that once called Wisconsin derisively the “laboratory of progressive reform.”

As the convention hall buzzed with tension, La Follette stood tall, his stern gaze surveying the sea of delegates. The air crackled with anticipation and the acrid scent of cigar smoke. When Roosevelt’s supporters, incensed by the machinations of the Taft camp, stormed out of the convention to form the Progressive Party, La Follette felt a pang of regret. He knew that his own intransigence had played a role in the schism, but he could not bring himself to abandon his principles.

The 1912 presidential race was a four-way battle of ideologies, with Taft, Roosevelt, Wilson, and Debs vying for the soul of the nation. La Follette, his heart heavy with the weight of the progressive cause, made the difficult decision to sit out the general election. As he watched from the sidelines, he couldn’t shake the feeling that this choice would haunt him in the years to come.

When the votes were tallied and Woodrow Wilson emerged victorious, La Follette felt a sense of foreboding. He knew that Wilson’s victory represented a setback for the progressive movement, and he couldn’t help but wonder if things might have been different had he chosen to unite with Roosevelt.

ANY WHICH WAY BUT WILSON

As Woodrow Wilson took office, his background as a scholar and statesman shaped his approach to the presidency. Wilson believed in a “living Constitution,” one that could be adapted to the changing needs and circumstances of the nation. However, this flexible interpretation of the Constitution would prove to be a double-edged sword

Wilson’s presidency was marked by a series of Progressive Era amendments, including the 16th, 17th, 18th, and 19th. These amendments reshaped the nation’s tax system, political landscape, and social fabric. But even as these progressive reforms took hold, Wilson’s own views on race cast a dark shadow over his administration.

A staunch segregationist, Wilson worked to roll back the progress that African Americans had made during Reconstruction. His policies reinforced racial discrimination and set the stage for decades of injustice. La Follette, a champion of civil rights, watched with growing dismay as Wilson’s actions undermined the very principles of equality and justice that the progressive movement had fought so hard to advance.

LA FOLLETTE AND SIXTEENTH

As the progressive movement gained momentum, La Follette recognized the need for a federal income tax to address the growing economic inequality in the nation. He saw the tax as a means to fund the progressive reforms he believed were necessary to create a more just and equitable society.

The fight for a federal income tax had a long and complex history in the United States. The Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan & Trust Co. decision had struck down previous attempts to implement such a tax, ruling that it was unconstitutional. But La Follette refused to let this setback deter him.

He threw his support behind the 16th Amendment, which would grant Congress the power to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states. La Follette worked tirelessly to build support for the amendment, using his oratorical skills and political savvy to make the case for progressive taxation.

In 1909, the 16th Amendment passed Congress, and by 1913, it had been ratified by the requisite number of states. The amendment overturned the Pollock decision and paved the way for the implementation of a federal income tax under the Revenue Act of 1913. For La Follette, the passage of the 16th Amendment was a hard-fought victory in the battle for economic justice.

A ONE MAN ARMY

As the drums of war began to beat louder, La Follette found himself once again standing against the tide of public opinion. A staunch believer in non-interventionism and anti-imperialism, he saw no justification for the United States to become entangled in the bloody conflict that was engulfing Europe.

In 1917, La Follette took to the Senate floor to filibuster against the Armed Ship Bill, which would have allowed American merchant ships to arm themselves against German submarines. For hours, he spoke passionately, his voice growing hoarse as he argued against the measure. But his efforts were met with a fierce backlash.

Branded a traitor and a German sympathizer, La Follette faced an onslaught of criticism and personal attacks. Effigies of him were burned on the University of Wisconsin campus, and he was denounced in newspapers across the country. But La Follette refused to back down, even as the Espionage Act and Sedition Act were passed, restricting civil liberties in the name of wartime security.

Throughout the war, La Follette remained a lone voice of opposition, his principles unwavering in the face of intense pressure to conform. His stance would cost him dearly but he knew that he could not compromise his beliefs, even in the face of such adversity.

THE NINETEENTH WHOLE

As Robert La Follette stood at the podium, his voice reverberating through the Senate chamber, he could feel the weight of the moment upon him. The speech he was delivering, a passionate defense of self-determination and the need for a more inclusive democracy, seemed to be falling on deaf ears, the senators more interested in their own conversations than the words of the fiery Wisconsin progressive.

But then, the chamber doors burst open, and in swept La Follette’s secretary, clutching a sheaf of papers. Hot on her heels were Belle La Follette and Wisconsin State Senator David James, their faces alight with a mixture of pride and relief. In James’s hands was the ratified 19th Amendment, a testament to the tireless work of suffragettes like his own daughter, Ada.

As La Follette took the document, he caught Belle’s eye, and a silent moment of understanding passed between them. This was the culmination of a long and difficult journey, one that they had undertaken together. Belle, the first woman to graduate from the University of Wisconsin Law School, had been a constant source of strength and inspiration for her husband, her own fierce commitment to women’s rights and progressive causes helping to fuel his own.

For La Follette, the 19th Amendment was more than just a political victory. It was a triumph of self-determination, a powerful rebuke to the idea, championed by President Wilson and others, that the Constitution was a tool for expanding executive and judicial power. In La Follette’s view, the Constitution was a living document, one that must evolve to meet the needs and aspirations of all Americans, not just the privileged few.

LA FOLLETTE FOR PRESIDENT…ENCORE

Four years later, as La Follette stood before the Progressive Party convention, accepting their nomination for president, he knew that he was embarking on the fight of his life. He had chosen to run on a platform of constitutional revivalism and self-determination, arguing that the Constitution must be a responsive, adaptable document that empowered the people to shape their own destinies.

This vision put him at odds with the likes of Wilson, who saw the living Constitution as a means to consolidate power in the hands of the executive and judiciary. But La Follette was undaunted, his voice ringing out with conviction as he painted a picture of a new kind of democracy, one in which every American had a say in the direction of their country.

Throughout the campaign, Belle was a constant presence at her husband’s side, her own formidable intellect and oratorical skills helping to win over skeptical voters. Together, they crisscrossed the country, speaking to packed halls and rallying supporters to their cause

In the end, though, it wasn’t enough. La Follette’s third-party bid fell short, though he did manage to capture an impressive 16.6% of the popular vote and carry his home state of Wisconsin. But even in defeat, the La Follettes knew that they had started something important, a movement that would continue to gather steam in the years to come.

DON’T CALL IT A COMEBACK

Returning to the Senate, La Follette threw himself into the fight for constitutional revivalism with renewed vigor. He introduced amendment after amendment, seeking to limit the power of the courts and expand the rights of the people. He spoke out against the Espionage Act and other wartime measures, arguing that they represented a dangerous erosion of civil liberties.\

Through it all, Belle remained a powerful ally and collaborator, using her own platform as a writer and activist to advance the cause of progressive reform. When Robert passed away in 1925, still serving in the Senate, many assumed that Belle would take his place. But she had other plans.\

Instead of accepting the appointment herself, Belle threw her support behind the couple’s eldest son, Robert Jr., who would go on to serve as a U.S. Senator for Wisconsin. Their younger son, Philip, would later be elected governor of the state, cementing the La Follette family’s legacy as a political dynasty.

For Belle, the decision to step back from elected office was a difficult one, but it was also a testament to her own commitment to the cause of constitutional revivalism. She knew that the fight would require the efforts of a new generation of leaders, and she was determined to do everything in her power to support and guide them.

A SELF-DETERMINED LEGACY

In the years following Robert La Follette’s death, his legacy lived on through the work of his sons and the countless activists and reformers who had been inspired by his example. Under the leadership of Robert Jr. and Philip, Wisconsin became a national model for progressive reform, implementing a range of innovative social programs that put the needs of the people first.

But the La Follettes’ impact extended far beyond the borders of Wisconsin. Their ideas and rhetoric helped to shape the course of American politics in the 20th century, influencing leaders like Franklin D. Roosevelt and paving the way for the New Deal. One of the most significant of these was the unemployment compensation program, which was made possible by the passage of the 16th Amendment and the institution of a federal income tax. First implemented by Governor Philip La Follette, it was the model for the version passed by the 1935 Social Security Act.

At the heart of this legacy was a deep commitment to the idea of the Constitution as a living, evolving document, one that must be constantly adapted to meet the needs of a changing society. For the La Follettes, this wasn’t just a matter of abstract principle, but a moral imperative, a sacred trust that had been handed down to them by generations of Americans who had fought and sacrificed for the cause of self-determination.

Today, as America faces new challenges and uncertainties, the legacy of the La Follettes and the idea of constitutional revivalism are more relevant than ever. As the author argues, the time has come for a 28th Amendment, one that would enshrine the right to self-determination as a fundamental principle of American democracy.

Such an amendment would be a fitting tribute to the work of Robert and Belle La Follette, and to the countless other activists and reformers who have fought to make the Constitution a true reflection of the will of the people. It would also serve as a powerful reminder that the fight for a more just and equitable society is never truly won, but must be renewed and carried forward by each successive generation.

Achieving this goal will not be easy. It will require the same kind of grassroots mobilization and tireless advocacy that characterized the La Follettes’ own efforts. But as their story reminds us, no obstacle is too great, no challenge too daunting, when the cause is just and the stakes are high.

So let us take up the banner of constitutional revivalism once more, let us fight for a 28th Amendment that would truly empower the people to shape their own destinies. Let us honor the legacy of Robert and Belle La Follette, and all those who have struggled and sacrificed for the cause of self-determination.

For in the end, this is the true meaning of the living Constitution, the beating heart of American democracy. And it is a cause that we must embrace with all the courage and conviction we can muster, knowing that the future of our nation depends on it.

TAKEAWAY: Robert La Follette’s unwavering commitment to self-determination and constitutional revivalism, as exemplified by his support for the 19th Amendment and his 1924 presidential campaign, highlights the need for a 28th Amendment enshrining self-determination as a fundamental right, in contrast to Woodrow Wilson’s view of the living Constitution as a means to embolden the executive and judiciary.