I: A Familiar Tension

As the spring semester draws to a close, the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus buzzes with anticipation for the upcoming commencement ceremony. Graduating students eagerly prepare to don their caps and gowns, while proud families make travel arrangements to celebrate their loved ones’ achievements. However, not everyone is ready to celebrate.

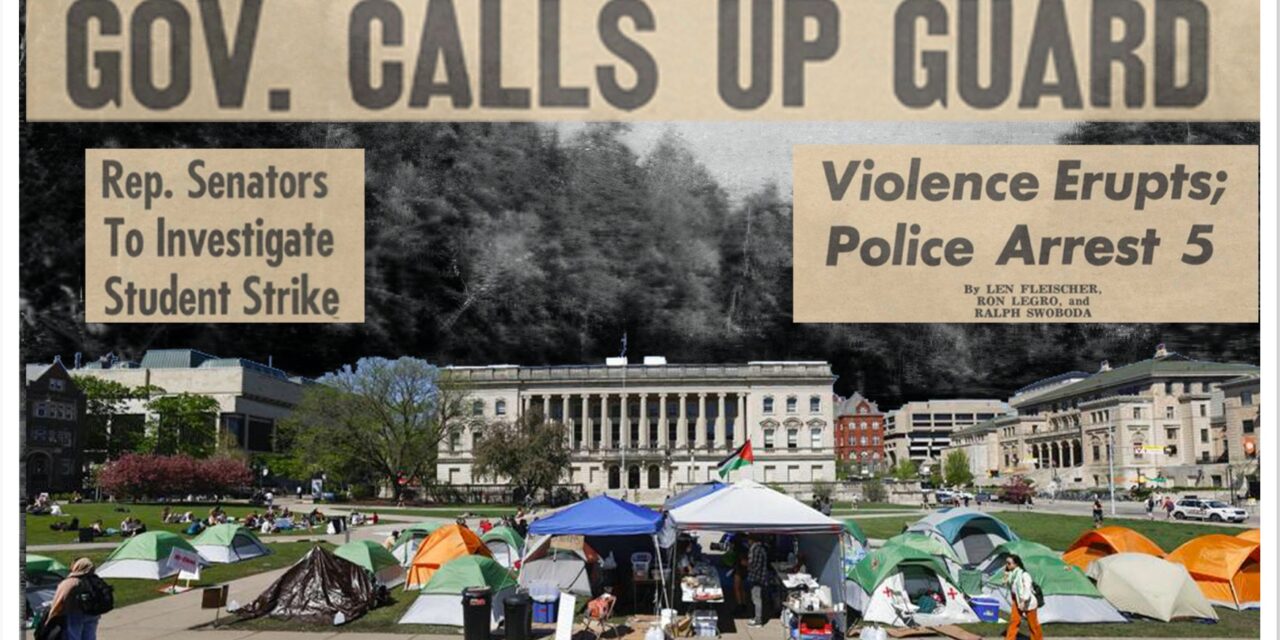

For weeks, pro-Palestinian student protesters have maintained a steadfast presence on Library Mall, their makeshift encampment a stark reminder, practically fractal like example of the unresolved conflict in Gaza that has engulfed the university. The students, united in their demand for divestment and transparency in the university’s investments, have clashed repeatedly with an administration seemingly unwilling to yield to their demands.

As the standoff continues, the debate over institutional responsibility and ethical investments has grown increasingly heated. Supporters of the protesters argue that the university has a moral obligation to divest from companies and institutions that perpetuate human rights abuses and contribute to the ongoing oppression of Palestinians. They point to the university’s stated commitment to social justice and equality, questioning how such values can be reconciled with financial ties to organizations complicit in the suffering of others.

On the other hand, the administration maintains that the university’s investment decisions are complex and cannot be easily untangled without significant financial and legal ramifications. They argue that the endowment must be managed in a way that ensures the long-term stability and success of the institution, and that political and social considerations cannot be the sole driving force behind investment strategies.

As the two sides remain at an impasse, the central question that has emerged from the controversy looms large over the campus: Who are universities really investing in?

II. The Dow Chemical Protest (1967)

The year was 1967, and the United States found itself mired in the quagmire of the Vietnam War. As the conflict escalated, so too did the protests against it, with college campuses across the nation becoming hotbeds of resistance. At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the anger and frustration reached a boiling point on October 18, when students gathered to demonstrate against Dow Chemical, the manufacturer of napalm, a highly flammable gel used in the war.

The air was thick with tension as hundreds of students converged on the Commerce Building, their voices rising in a chorus of indignation. They carried signs emblazoned with slogans like “Dow Shall Not Kill” and “Napalm Burns Babies,” their words a searing indictment of the company’s complicity in the war’s atrocities. The protesters, many of them members of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), demanded that the university sever its ties with Dow and other companies profiting from the conflict.

As the demonstration grew in size and intensity, the police presence on campus swelled. Officers in riot gear, their faces obscured by helmets and gas masks, formed a menacing phalanx around the building. The stage was set for a confrontation that would become known as one of the first violent campus protests of the era.

The clash began with a push, a shove, a moment of confusion that quickly escalated into chaos. Police wielding batons and tear gas canisters surged forward, their actions fueled by a potent mix of fear and aggression. Students, caught off guard by the sudden onslaught, fought back with whatever they could find – rocks, sticks, and their own bodies, throwing themselves into the fray with a desperate, righteous fury.

The air burned with the acrid tang of tear gas, and the sounds of shattering glass and screams of pain mingled with the chants of the protesters. In the midst of the mayhem, a young man named Ben Masel, a leader of the SDS, stood atop a car, his voice hoarse from shouting. “Dow shall not kill!” he cried, his words a rallying cry for the students who fought on, even as the police closed in around them.

When the smoke cleared and the dust settled, the toll of the protest became clear. Dozens of students and police officers had been injured, some seriously. The Commerce Building lay in shambles, its windows smashed and its walls scarred by the violence that had unfolded within and around it.

In the aftermath of the protest, the university community grappled with the implications of what had transpired. For many students, the event was a wake-up call, a stark reminder of the power of collective action and the lengths to which the establishment would go to maintain the status quo. The protest had laid bare the deep divisions that existed within the university and the nation as a whole, and it had raised uncomfortable questions about the role of higher education in perpetuating the military-industrial complex.

For the administration, the Dow Chemical protest was a public relations nightmare, a black eye that threatened to tarnish the university’s reputation. In the days and weeks that followed, officials scrambled to contain the fallout, issuing statements and holding meetings in an attempt to quell the growing unrest on campus.

But the damage had been done, and the seeds of change had been planted. The Dow Chemical protest had exposed the university’s ties to companies profiting from war and raised awareness of the need for greater transparency and accountability in institutional investments. It was a watershed moment in the history of student activism at UW-Madison, one that would pave the way for future movements and demonstrations, each building upon the legacy of those who had come before.

As the university community struggled to come to terms with the events of October 18, 1967, one thing became abundantly clear: the question of who universities invested in was one that could no longer be ignored. The Dow Chemical protest had shattered the illusion of neutrality and forced the institution to confront the moral implications of its financial ties. It was a reckoning that would continue to shape the course of student activism at UW-Madison for decades to come.

III. The Black Student Strike (1969)

Less than two years after the violent clash over Dow Chemical, the University of Wisconsin-Madison found itself embroiled in another campus upheaval. This time, the catalyst was not a distant war but a homegrown injustice: the pervasive racial inequities that had long plagued the university and the nation as a whole.

Frustrated by the administration’s intransigence, the BSA took action. On February 7, 1969, a group of Black students marched into the office of Chancellor H. Edwin Young, their faces etched with determination. They presented the chancellor with an ultimatum: meet their demands, or face the consequences of a campus-wide strike. These demands included:

- The creation of a Black Studies department

- The admission of at least 500 Black students for the fall semester of 1969

- The recruitment of more Black faculty and staff

- The establishment of a Black cultural center

- The creation of a Black student housing cooperative

- The development of a Black student orientation program

- The hiring of a Black counselor and a Black financial aid officer

- The allocation of funds for Black student scholarships and grants

- The removal of police from the campus

- The end of university contracts with companies that discriminated against Black people

- The establishment of a Black student judiciary board

- The creation of a Black student radio program

- The immediate enrollment of any expelled Oshkosh students who wished to attend UW-Madison

In the months leading up to the Black Student Strike at UW-Madison, another protest at the Wisconsin State University-Oshkosh (now UW-Oshkosh) had a significant impact on the growing student movement. On November 21, 1968, 94 Black students at WSU-Oshkosh, known as the “Oshkosh 94,” staged a demonstration in the office of President Roger Guiles. The students presented a list of demands aimed at addressing the lack of Black faculty, the need for Black studies courses, and the discrimination faced by Black students on campus. The protest turned violent, with damage to property in the president’s office, leading to the arrest of the demonstrators.

The fallout from the Oshkosh protest was swift and severe. The administration, backed by the local media and conservative politicians, moved to expel 90 of the 94 students involved, sparking outrage among civil rights activists and progressive students across the state. The Black students at UW-Madison, many of whom had connections to the Oshkosh activists, saw in the harsh response to the protest a reflection of the deeply entrenched racism and resistance to change that permeated the higher education system in Wisconsin.

The atmosphere in the chancellor Young’s office was electric, the air heavy with the weight of the moment. Young, a bespectacled man with a reputation for firmness, listened impassively as the students laid out their grievances, his expression betraying little emotion.

The students, undeterred by the chancellor’s response, pressed on. They argued that the university had a moral obligation to address the systemic barriers that had long prevented students of color from accessing the full benefits of a college education. They spoke of the daily indignities they faced on campus, from the casual racism of their white peers to the lack of representation in the curriculum and the faculty.

Some of the students began to shout, their voices raw with anger and frustration. Others wept, overcome by the emotions of the moment. Through it all, the chancellor remained impassive, his face a mask of inscrutability.

In the end, the meeting ended in a stalemate, with neither side willing to budge. The Black students, their demands unmet, walked out of the chancellor’s office, their resolve hardened by the encounter. They knew that the road ahead would be long and difficult, but they were prepared to fight for as long as it took to achieve justice.

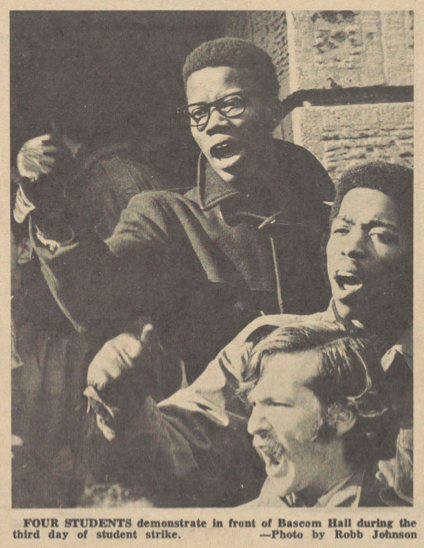

Over the next several weeks, the Black Student Strike took hold of the campus, as hundreds of students boycotted classes and staged demonstrations in support of the BSA’s demands. The striking students, clad in black and with fists raised in solidarity, marched through the streets of Madison, their chants echoing off the walls of the stately buildings that lined the route.

Despite the growing pressure from the students and their allies, the administration remained largely unmoved. Chancellor Young, in a series of public statements, acknowledged the need for greater diversity and inclusion on campus but stopped short of committing to the specific demands of the BSA. Instead, he offered a series of incremental reforms, such as the creation of a task force to study the issue of race on campus and the allocation of additional funding for minority recruitment efforts.

To the striking students, these half-measures were woefully inadequate. They saw in the administration’s response a familiar pattern of lip service and inaction, a continuation of the same cycle of oppression and marginalization that had defined the Black experience on campus for generations.

As the strike wore on, tensions continued to mount. Police in riot gear patrolled the streets, their presence a constant reminder of the state’s willingness to use force to maintain order. Some of the striking students were arrested, their bail money raised by a network of supporters who saw in their struggle a reflection of the larger fight for civil rights that was playing out across the nation.

Despite the lengthy list of demands and the sustained pressure from the striking students, the university administration ultimately met only two of the 13 demands in full. The first was the creation of a Black Studies program, which eventually became the Afro-American Studies Department. The second was the establishment of a Black cultural center, now known as the Black Cultural Center.

While these concessions represented important victories for the striking students, the failure to achieve the full scope of their demands underscored the deep-seated resistance to change within the university and the ongoing struggle for racial justice that would continue for decades to come.

IV. The Pro-Palestinian Demonstrations (2024)

As the spring of 2024 unfolds, the University of Wisconsin-Madison finds itself once again at the center of a student-led protest movement. This time, the issue at hand is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the university’s investments in companies and institutions that protesters claim are complicit in the oppression of Palestinians.

The students, organized under the banner of “UW Divest,” have set up an encampment on Library Mall, the same site where, more than half a century earlier, protesters gathered to demonstrate against the Vietnam War and the university’s ties to Dow Chemical. The encampment is a sea of colorful tents and hand-painted banners, a vivid testament to the passion and dedication of the young activists who have made it their temporary home.

At the heart of the encampment is a makeshift stage, where student leaders take turns delivering impassioned speeches and leading chants of solidarity. Their voices are strong and clear, cutting through the cool, damp air of the Wisconsin spring. They speak of the daily injustices faced by Palestinians living under Israeli occupation, of the destruction of homes and the displacement of families, of the constant fear and uncertainty that comes with life in a war zone.

As the demonstrations gather steam, the atmosphere on campus grows increasingly tense. Counter-protesters, some wielding Israeli flags and chanting slogans of their own, clash with the UW Divest activists, their verbal sparring matches occasionally erupting into physical altercations. The police, clad in riot gear and armed with batons and pepper spray, maintain a watchful presence, ready to intervene at a moment’s notice.

For the university administration, the protests pose a thorny dilemma. On the one hand, they are committed to the principles of free speech and open dialogue that are the hallmarks of a liberal arts education. They recognize the importance of allowing students to express their views and engage in peaceful protest, even when those views may be controversial or unpopular.

On the other hand, the administration is acutely aware of the financial and political pressures that come with managing a large public university. They know that any move to divest from companies with ties to Israel would likely be met with fierce opposition from donors, alumni, and state legislators, many of whom see such actions as a form of anti-Semitism.

As the protests drag on, the administration finds itself caught between a rock and a hard place. They issue carefully worded statements expressing support for the students’ right to protest while reaffirming the university’s commitment to academic freedom and the free exchange of ideas. They meet with student leaders behind closed doors, seeking to find common ground and a way forward that will satisfy all parties.

But the protesters are not easily placated. They see in the administration’s equivocation a familiar pattern of inaction and complicity, a refusal to take a stand on an issue of moral urgency. They point to the university’s past failures to address issues of racial and social justice, from the unmet demands of the Black Student Strike to the ongoing struggle for equity and inclusion on campus.

As the semester draws to a close and commencement looms on the horizon, the protests show no signs of abating. The UW Divest activists, their resolve hardened by months of struggle and sacrifice, vow to continue their fight until the university meets their demands for divestment and transparency.

In many ways, the pro-Palestinian demonstrations of 2024 are a reflection of the long and complex history of student activism at UW-Madison. They are a reminder of the power of collective action and the enduring legacy of those who have come before, from the anti-war protesters of the 1960s to the Black student activists of the 1970s.

But they are also a testament to the ongoing struggle for justice and equality in a world that often seems resistant to change. As the university community grapples with the implications of the protests and the larger questions they raise about the role of higher education in promoting social and political progress, one thing remains clear: the fight for a more just and equitable future is far from over.

SIMPLY PUT:

The parallels between the Dow Chemical protest of 1967 and the current pro-Palestinian demonstrations at UW-Madison are striking. In both cases, students are challenging the university’s financial ties to entities they view as complicit in human rights abuses and oppression. The protesters argue that by investing in or partnering with these entities, the university is betraying its stated values and becoming complicit in the suffering of others.

This represents a significant shift in the focus of student activism, from targeting the government and military to holding universities and corporations accountable for their financial relationships. It reflects a growing awareness of the complex web of institutional ties that underlies many social and political issues and the power that students and activists have to effect change by pressuring these institutions to align their investments with ethical considerations.

What is the role of universities in promoting social and political progress? How can institutions balance their financial obligations with their moral responsibilities? And what is the enduring legacy of student activists who have fought to hold their universities accountable and shape a more just and equitable future?