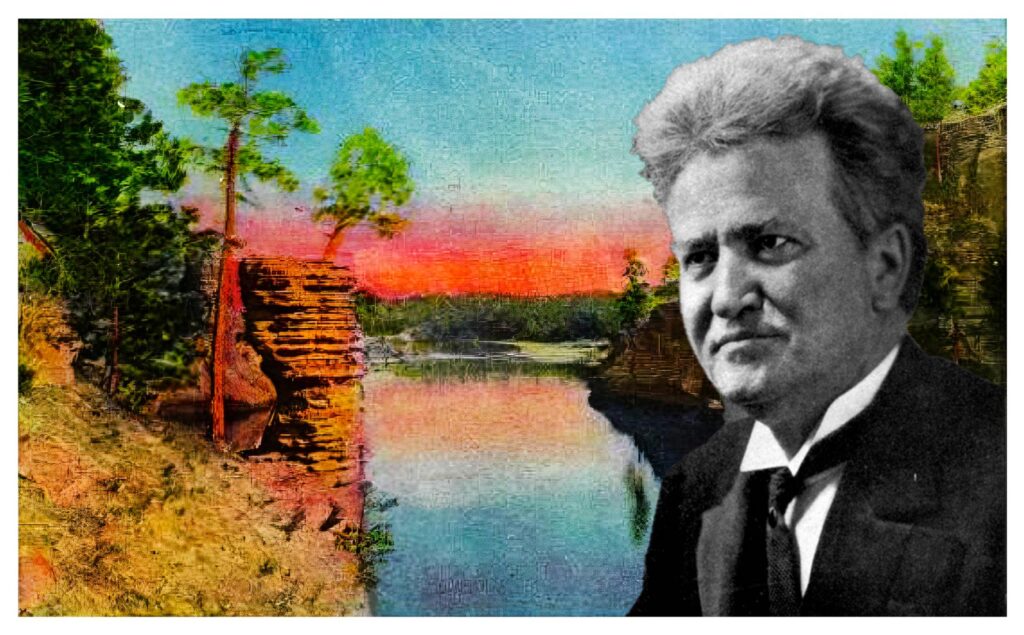

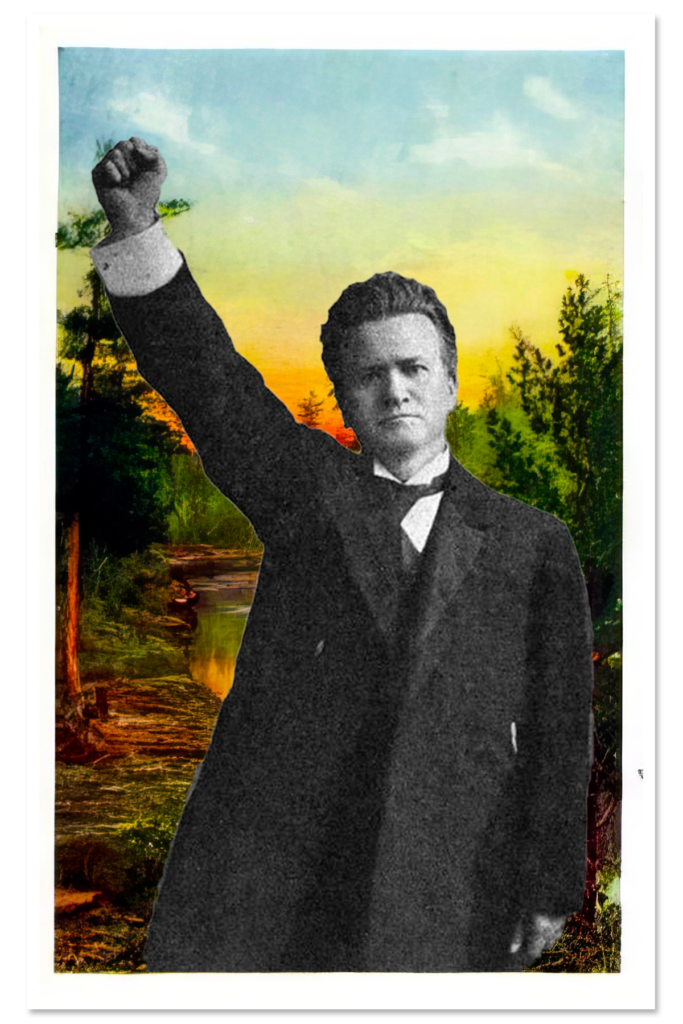

The progressive faction of the Republican Party in Wisconsin, founded by Robert M. La Follette, Sr. in 1894, played a crucial role in shaping the state’s politics for 40 years. La Follette, who served as a U.S. Representative, Governor of Wisconsin, and U.S. Senator, fought against party bosses and corrupt practices throughout his career.

La Follette’s progressive movement led to the passage of several important pieces of legislation, including the direct primary law, railroad taxation, the creation of a railroad commission, and the income tax. He ran for president in 1924 as a Progressive Party candidate, receiving a record 5 million votes for a third-party candidate at the time.

After La Follette’s death in 1925, his sons, Robert Jr. and Philip, continued the progressive movement in Wisconsin. However, the Great Depression and the rise of the Democratic Party under Franklin D. Roosevelt contributed to the decline of the progressive faction in the 1930s.

Timeline:

1894: Robert M. La Follette, Sr. founds the progressive faction of the Republican Party in Wisconsin.

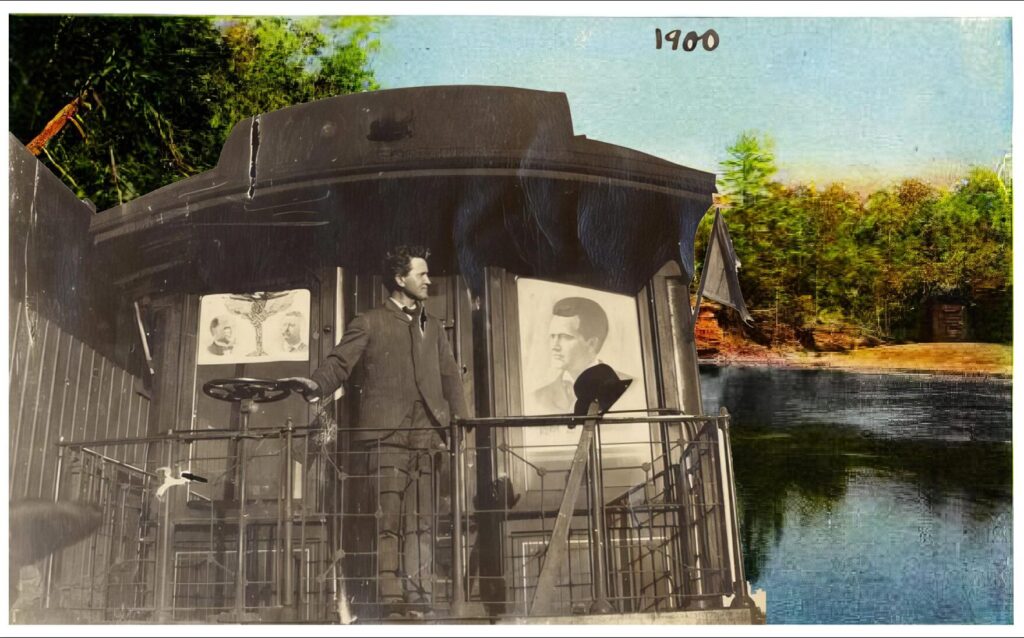

1900: La Follette is elected Governor of Wisconsin.

1905: La Follette is elected to the U.S. Senate.

1912: The progressive-led legislature passes several key pieces of legislation, including the income tax law and the workmen’s compensation act.

1924: La Follette runs for president as a Progressive Party candidate, receiving 5 million votes.

1925: Robert M. La Follette, Sr. dies; his sons continue the progressive movement.

1930: Philip La Follette is elected Governor of Wisconsin.

1932: Franklin D. Roosevelt is elected president, marking the rise of the Democratic Party.

1934: The progressive faction loses ground in Wisconsin politics.

THE MILWAUKEE JOURNAL

Chapter of Wisconsin History Ends as Progressive Faction Disappears

Born of Revolt Against ‘Boss Rule,’ the La Follette Movement Grew, Conquered and Waned; Its Influence Was Nation-Wide

By H. P. RINGLER of the Journal Staff

Today marks the end of an era in Wisconsin history; it is a momentous day. Today the progressive faction of the Republican party—the personalities and campaigns and legislation of which have been the history of Wisconsin for 40 years—is no more. Its followers decided at Fond du Lac yesterday to leave the Republican camp and join in the creation of a third party.

Political factions, bred in discontent with the old established parties, have risen and fallen many times in American history. Few have had much influence in guiding the course of national events. The progressive faction of Wisconsin is one of those few. The progressive movement was no skyrocket; for four decades it was the predominating influence in Wisconsin politics.

One presidential candidate and leader whose influence was felt nationally, five United States senators, five governors, many congressmen, state legislators, state officers and department heads—these the progressive faction contributed to nation and state.

La Follette, the elder, the founder, the leader; his two sons, Lenroot, Stephenson, Blaine, McGovern, Ekern, Davidson, Morris, Dahl, Hatton, Haugen, Frear—these are but a few of the many men of nation and state, the best known to the progressive faction.

The roll could go on for pages. The greater part of the front ranks. Some deserted; some were booted out, but they all have left their mark on the political stage with legislation therein is of progressive sponsorship of the faction been called radical, but it has come on the political stage with first called radical, but it has come on the political stage with first called by many other commonwealths and is today considered that today is no more.

It was just 40 years ago—in 1894—that Robert M. La Follette, sr., sensing the discontent of the agrarian population of Wisconsin with boss and lobby rule, founded the progressive faction of the Republican party. For 31 years, until his death in 1925, he held the leadership firmly.

There are those who say that were the senior La Follette alive there would be no third party being formed; there would be no such agitation. They imply that the succeeding leadership of the progressive faction did not wield the power as ably or firmly as did the founder.

The senior La Follette always opposed the formation of a third party in state politics. Even when he ran for the presidency in 1924 as a progressive party candidate he saw to it that his followers in Wisconsin remained in the Republican ranks.

No Farm Revolt Then

But La Follette, sr., never faced a revolt of the farm lands. He did not live to see wholesale farm foreclosures and evictions of milk strikers with troops, armed with clubs and tear gas, called out to keep the highways clear of farm holiday pickets. He did not live to see the renaissance of the Democratic party in Wisconsin—the party that he kept at low ebb and nearly destroyed. These, and a hundred other problems that confronted his successors, he did not know. If he had—well—here is what he said in his autobiography, speaking of the 1896 campaign:

“Many of my close advisers, too, believe that we should try to break from the Republican organization and try to build up a new reform party in the state. But I do not believe that it lies in the power of any one man or group of men successfully to proclaim the creation of a new political party. New parties are brought forth from time to time. But the leaders did not create the party. It was the ripe issue of events. No one can foretell the coming of the hour. It may be at hand. It may be otherwise. But if it should come quickly, we may be sure strong leadership will be there.”

ROBERT M LA FOLLETTE, SR

Chapter of History

Perhaps it is foolhardy to write an obituary of the progressive faction. For the third party may fail and disappear and in two or four or more years its leaders may be back in the Republican primaries fighting the stalwarts. But today, practically at least, marks the demise of the faction and now is the time to review its victories and its defeats, its personalities, its internal battles, its tragedies and its comedies.

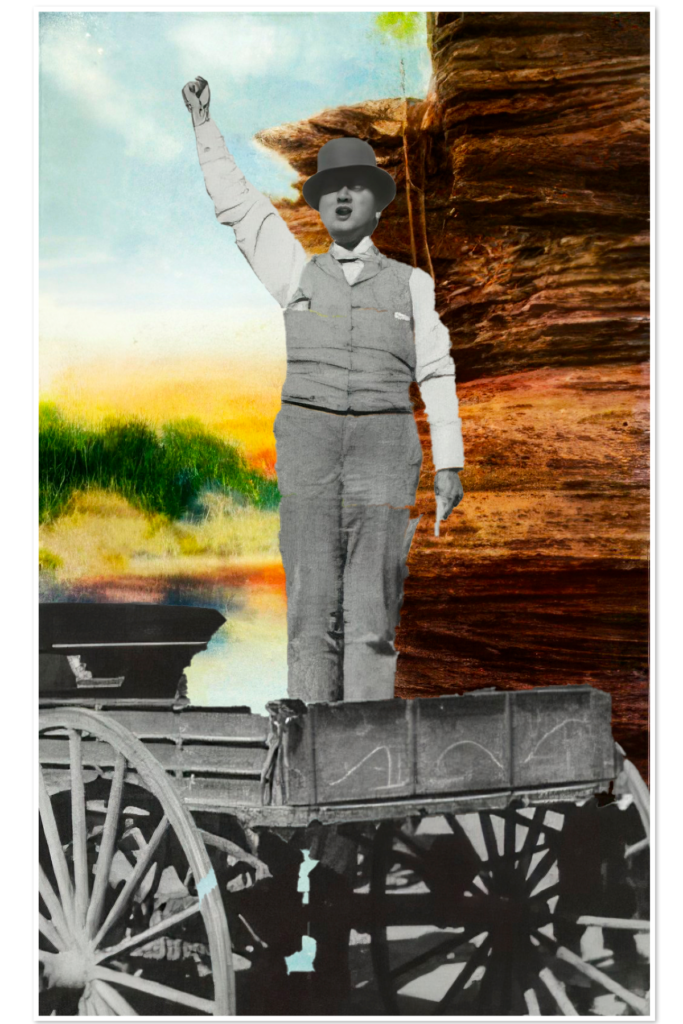

There can be but few citizens of Wisconsin who do not know the stirring story of the events that brought about the birth of the progressive faction, how Bob La Follette, only 25, just out of law school, decided Dane County’s Assembly, W. W. Keyes, ran for district attorney and won by 93 votes. That first campaign was a harbinger of many to come. La Follette, even then combing his black hair in that pompador style that was to become famous, was trying to reach every farmer in the county, chatting with them from his buggy or writing them letters. Re-elected in 1882—the only successful Republican—and in 1884 a candidate for congress. Elected by 400 votes. Re-elected in 1886 and 1888, always over opposition of the bosses. In 1890, confident of victory, unaware that all was not well at home, he spoke in Iowa—and elsewhere. The Bennett Law had been passed, Wisconsin Lutherans and Catholics saw it as a blow at their parochial schools, and cut the Republican ticket. Every Republican congressman lost.

Philetus Sawyer Case

La Follette returned to private practice. In 1891 came the famous treasury cases and the equally famous “bribe” charge against United States Senator Philetus Sawyer, one of the old guard bosses. The Milwaukee Journal had demanded that action be taken to make recent state treasurers return interest on public funds which they had retained as a political perquisite. The Democratic Peck administration started lawsuits. Judge Robert G. Siebecker, La Follette’s brother-in-law and law partner, was to hear the cases.

La Follette was asked to meet Sawyer in Milwaukee. Sawyer was a bondsman for several of the treasurers and stood to lose heavily if the case was lost. The two men met at the Plankinton House. La Follette charged later that Sawyer offered him a bribe to influence Siebecker’s decision. Sawyer denied this, insisting that he had offered La Follette a retainer in the case, not knowing he was a relative of the judge. Siebecker withdrew, another judge presided, and ruled against the treasurers.

La Follette was much criticized. Followers demanded that he run as an independent, “but I convinced them,” La Follette later wrote, “that if any one was forced to leave the Republican party it should be the corrupt leaders.”

His experiences in the 1896 convention caused La Follette to determine on the overthrow of the caucus and convention system.

Victory for His Platform, Anyway

La Follette established The State, a weekly. It was his first so-called medium of education. Its greatest scoop was the revelation that Gov. Schofield had a cow shipped from Oconto to Madison under his express frank. “Schofield’s cow” was the most famous cow in the state’s history—there was such ridicule and resentment that a bill for the abolition of franks and railroad passes was passed in the legislature.

In 1898 La Follette offered to support any progressive who would run, but no one would, so he again entered the lists. He charged that as much as $8,300 was used to defeat him in the convention, but he succeeded in getting the progressive platform accepted. Schofield was re-elected.

By 1900 the La Follette ideas had so permeated the state that his victory in convention and state was foreseen. Stalwart candidates who ran in local caucuses were swamped. Stalwart leaders, Isaac Stephenson, E. L. Philipp, J. W. Babcock, got on the band wagon. Stephenson, it was said, was angry at the Old Guard for not giving him the United States senatorial nomination. La Follette was nominated with no real opposition. He campaigned on two issues: a direct primary law and railroad taxation. He defeated Louis G. Bomrich, Democrat, easily.

Two days after the inauguration the word “stalwart” was first used in Wisconsin politics—a group of “stalwart” Republican legislators announced that they controlled both houses and would fight all administration plans.

Battle of Newspapers

The Milwaukee Sentinel, which had been backing the La Follette cause, was purchased by Charles Pfister. Pfister’s new editor came to the governor and said the Sentinel would begin “skinning” him unless he let up; La Follette derided the Sentinel and it became his most vigorous editorial foe. To combat the Sentinel, Isaac Stephenson founded the Milwaukee Free Press.

La Follette charged that bribes were given legislators by the lobbyists as a substitute for his primary bill. A sent to the governor and he vetoed it. “In legislation,” he wrote of this later, “no bread is often better than half a loaf.” A bill was passed taxing dogs and La Follette, in a scathing message, pointed out the “ridiculousness” of increasing taxes on the poor and middle class while allowing the railroads and other corporations to escape just taxation. Nevertheless, his rail tax bills were killed.

Before adjourning more than half the members of both houses signed a manifesto criticizing the governor for “encroachment upon the constitutional rights of the legislative branch.” La Follette had a breakdown immediately, the legislature adjourned and was ill for a year.

Eleventh Story League

In 1902, stimulated by their successes in the legislature, the stalwarts made a terrific fight on La Follette. They established headquarters on the eleventh floor of the Railway Exchange building, Milwaukee, and the campaign is known as that of the “Eleventh Story League.” Senator John Whitehead of Janesville was their candidate. La Follette depended on his speeches and a “Voter’s Handbook,” which described the progressive plans and charged the opposition with corrupt methods. Of this 125,000 copies were distributed. La Follette won the nomination and defeated David Rose, Milwaukee, the Democrat, easily in the election.

The 1903 legislative gave Wisconsin its first progressive laws. In his message the governor roundly scored the railroads and demanded a regulatory body and revised railroad taxation. His message was called unfair. He sent in another, comparing rail road rates in Wisconsin with those of neighboring states, showing that Wisconsin’s “suffered by the comparison.” The lobby was so worried about the regulatory bills that it forgot about the tax measures, which were passed, increasing the state income $600,000 annually.

The primary election bill went through, with a rider providing for a referendum in 1904. An inheritance tax bill was passed and corporation taxes were increased. A bill to purport practices bill and anti-lobby bill were defeated. The state-insurance fund was created. La Follette’s legislative leader was a comparatively unknown Superior man, Irvine L. Lenroot.

Strength of 1904; The Crucial Year

“The crucial year”—that was 1904. The campaign started a year early. Two stalwarts, Emil Baensch, former lieutenant governor, and S. A. Cook, Neenah lumberman, were in the race. They fought La Follette as a radical; they insisted he was violating a “no third term” tradition. La Follette stumped the state, using two automobiles. Once he spoke 48 days in succession, excepting Sundays. He read the legislative roll calls for the first time in Wisconsin—as a procedure that has stood the party leaders in good stead many times.

What was probably the most exciting convention in the history of the state occurred at Madison in the old red gymnasium on the shore of Lake Mendota. The progressives had heard that second slates of delegates were being chosen at rum conventions. The day before the convention the state central committee, controlled by the La Follette men, considered the contests and seated the La Follette delegates.

The progressives prepared to have the convention “rushed.” A barbed wire fencing was put up at the delegate entrance to prevent rushing. Husky university football men—Arnze Leraun, Nosky Larson, Bill Hank and Fred Krull and others—took possession at the gate. The stalwarts marched down from Capitol square and were halted at the barbed wire entrance. When an unrecognized delegate came up he was refused entrance.

Stalwart “Rump” Meeting

The stalwarts were licked and knew it. After Lenroot had been named chairman, a leading stalwart rose and announced there would be a meeting that night of “anti-third termers” at the Fuller opera house, now the Parkway theater. At that rump convention Baensch withdrew and Cook was nominated to run against La Follette.

Delegates at large were picked by both groups to attend the Republican national convention. There the stalwarts were seated.

The stalwarts started action against Secretary of State Walter Houser, a La Follette man, to force him to certify the names of candidates. A slate as the Republican to the Secretary was carried to the Supreme court and the progressive ticket was ruled the regular ticket; Cook stayed in the race, the stalwarts knifed him, and supported…

Peck, the Democrat, but La Follette won easily. His complete slate went in and for the first time he was given control of the legislature. The primary election bill was overwhelmingly approved.

Chosen United States Senator

The first act of the 1905 legislature was to choose La Follette United States Senator, to succeed J. V. Quarles. Even the stalwarts voted for the governor; it was said they wanted to get rid of him. For a while it seemed doubtful if La Follette would accept; finally he said he would, but “the job at home must be finished first.”

The 1906 legislature passed the railroad commission bill, the civil service commission bill, and the constitutional amendment providing for an income tax was approved for the first time. Concurrently with New York, Wisconsin investigated the insurance companies. Herman L. Ekern, a young attorney, leaped into prominence as the probe leader. The old capitol had burned in 1904 and the appropriations for the present beautiful structure were approved. A sensational preference primary bill was passed.

Late that year La Follette went to Washington to take the senate seat he held until his death. Most of his time from then forth was spent in the capitol, but his control over the progressive faction at home never wavered.

La Follette Man Beaten by Voters

Lieut. Gov. James O. Davidson, Norwegian from Soldiers Grove, became governor. La Follette, in 1906, chose Lenroot, his speaker of the house in 1903 and 1905, for the gubernatorial candidacy. But Davidson fought to hold his job and the stalwarts, overjoyed at dissension in the enemy ranks, backed Davidson, who won easily. La Follette learned then that Wisconsin voters cheered him, but did not always follow his advice.

The 1907 legislature was progressive. Ekern put through the insurance regulatory laws. The highway commission was created; public utilities were put under the railroad commission. The income tax amendment passed again. Davidson, inspired that he was a progressive, approved all these measures.

During the session United States Senator John C. Spooner resigned. There was a heated contest in the legislature, with La Follette paying his political debt by supporting Isaac Stephenson. John Esch and Henry Allen Cooper were other candidates. Stephenson won, and there were rumors of questionable dealings.

There was little organized opposition to Davidson in the 1908 campaign. The fight was all in the senatorial preference primary. Stephenson was seeking re-election. La Follette forces, explaining that they promised Stephenson only the rest of Spooner’s term, entered State Senator W. H. Hatton, New London, and Francis E. McGovern in the race. Hatton was a La Follette leader; McGovern had become noted as the district attorney of Milwaukee county, who conducted a graft investigation that “smeared” many stalwarts.

La Follette Stephenson Inquiry

La Follette was silent as to his choice. It was understood his leaders were for Hatton. Stephenson won with a minority vote. When the 1909 legislature adjourned, one of the first resolutions offered was that of a little known senator from Boston, John J. Blaine, demanding an investigation of the Stephenson campaign. Blaine cited the fact that Stephenson had admitted spending $107,000 and said it was his belief that some of this money was corruptly spent.

The senate was progressive, the assembly stalwart. Stephenson was by now an open stalwart. A committee was appointed and investigated. A majority said there was no fraud proved, a minority said in effect that there was plenty wrong; meanwhile the legislature had re-elected Stephenson.

Legislators told of receiving money from Stephenson aids and spending it to further their own candidacies. Few of them could give detailed accountings of the way they spent the money. For years afterwards, La Follette forces were using the testimony in this investigation to defeat legislative candidates.

The Stephenson election was challenged in the United States senate; Stephenson was seated by a few votes, La Follette voting against him.

The year 1910 brought another senatorial preference primary and a state campaign. La Follette, who had broken with Taft, was assailed for his irregularity but he won easily. The primary was noteworthy because of the election of a dead man, Levi G. Bancroft, Richland Center, was stalwart choice for attorney general. He discovered that literature backing Tucker, his progressive opponent, had come out on paper from the attorney general’s office. Tucker was an assistant attorney general.

Bancroft cried “scandal.” Tucker, distracted, killed himself. The progressives demanded that he be vindicated in death, labeled Bancroft very objectionable, and said if Tucker were elected, the La Follette controlled state central committee could name the new attorney general.

Bancroft cried: “They’re trying to elect the ghost of a dead thief.” The voters elected McGovern governor, all of his state officers, including Tucker, and an overwhelming progressive legislature. A committee nominated Charles H. Crownhart to take Tucker’s place but Bancroft won a court ruling that votes for a dead man did not count; that Bancroft had a majority of the other votes and was thereby elected.

Flood of Laws at 1912 Session

The 1912 legislature was the greatest progressive body of Wisconsin’s history. It, of course, re-elected Senator La Follette. It passed the workmen’s compensation act, established the industrial commission, passed the income tax law, a new corrupt practices act, a women’s hours of labor law, the vocational education law, set up a state budget system and passed the bovine tuberculosis testing law. It also passed the “Mary-Ann” law, a second choice primary law which La Follette expected to help prevent stalwart minorities from electing a candidate when more than one progressive was in the field. Voters refused to make second choices, however, and the law was repealed. La Follette then found it necessary to endorse candidates.

In 1912 La Follette was a candidate for the presidency. He hoped to win the Republican nomination from Taft, but after he had built up a national organization Theodore Roosevelt entered the field and won over most of his followers and the Progressive forces; after defeat in the Chicago convention, help run a rump convention and organized the Bull Moose party.

Wisconsin was all for La Follette; his leaders were his campaign leaders. The delegation went to Chicago, pledged to him. There occurred the incident that split La Follette and McGovern.

Break With McGovern

The Roosevelt forces wanted McGovern named convention chairman. La Follette, seeing it as a plot to make it appear that his support would eventually go to Roosevelt, opposed the move. McGovern ran and was defeated.

In the presidential election itself, La Follette ran as the Progressive candidate. He crossed McGovern in the gubernatorial campaign. There was a story, never confirmed, that he told a friend, “I’ll take care of McGovern at the proper time.” McGovern backed Roosevelt. Many of the progressive leaders supported Woodrow Wilson, the Democrat, John Blaine even heading a Wilson Republican campaign committee. The campaign carried the state and very nearly brought the Democratic gubernatorial candidate, John C. (Ikey) Karel, in with him.

Ganfield, president of Carroll college, Waukesha, was his opponent in the primaries. Blaine, up for re-election, also “put on the heat.” With records from the tax commission he read the tax lists of large corporations in the state. W. J. Morgan was his opponent. The prohibition issue appeared for the first time. Given campaign funding by a Wisconsin Blaine vetoed the strict “Maeve” bill, and finally accepted the more liberal Severson measure. His candidacy and that of La Follette became that of the wets; Ganfield, personally a dry, put the prohibitionist stamp on the stalwarts.

La Follette and Blaine received the largest majorities ever given such candidacies in the state. The party fight was so intense that 20,000 Democrats were left off the final votes and ballot. Both won easily in the election.

La Follette Runs for Presidency

In 1924 Senator La Follette ran for president as a candidate of the Progressive Conference for Political Action. Blaine had his hands full with A. R. Hirst, who resigned as state highway engineer to run. Lieut. Gov. George F. Comings also got into the battle. Blaine beat Hirst, then the Democrat.

Wisconsin went overwhelmingly for La Follette for president. It was the only state he carried, although he received 5,000,000 votes, the greatest ever received by a third party candidate before or since. The arduous campaign broke his health.

The 1925 legislature passed a new income tax bill, with much higher rates, repealed the personal property tax offset, increased the aid to schools, voted publicly for income tax returns, and passed a highway bill creating a gasoline tax and providing that the proceeds be used for local roads and streets as well as for verbal blasts at the Ku Klux Klan man.

Death and Successors

In June, 1925, “Fighting Bob” La Follette died. Then followed the war of the succession. Candidates came out right and left. Many wanted Mrs. La Follette to run, for she had long been considered one of the keenest political minds in the faction. But she refused and said that Robert Jr., should be the candidate. Her voice prevailed and the elder son, who had been in poor health for many years, was chosen, most of the others withdrawing. He won easily in the primary and in the election.

For the next year brought Lenroot up for re-election as United States Senator. Blaine entered the lists. The La Follette men, still plotting since their leader’s death, gathered behind their governor. Fred R. Zimmerman, secretary of state, had been aiming at that office for years. He jumped in: It was a knock-down fight on all fronts.

Blaine flayed Lenroot as a conservative, a betrayer of the elder La Follette, and, to the surprise of many, won. Zimmerman, with his incredible knack for hand shaking and remembering faces and names, combined with the publicity he had received as a result of being in charge of the issuance of auto licenses, won over the dignified and stolid Ekern. The klan was a strong factor in Zimmerman’s victory. The stalwarts had nominated Charles B. Perry of Wauwatosa, but they deserted him for Zimmerman.

The Zimmerman legislative session found the progressives in full opposition. Zimmerman, who promised all things to all men, and who admitted that he’d consulted an astrologer as to affairs of state, steadied lost ground.

In 1922 a new personality entered Wisconsin politics—the Moses that the stalwarts had been seeking since Philipp’s time. He was Walter J. Kohler, the bathtub manufacturer. He ran for governor. The progressives ran Congressman Joseph D. Beck, Viroqua, and Zimmerman sought re-election.

Coolidge prosperity was at its height. Hoover was elected on the slogan of “A chicken in every pot,” and Kohler, who campaigned in an airplane, walked in the primary. Beck was second. Zimmerman a very poor third. A. G. Schmedeman opposed Kohler in the election and, aided by a heavy vote for Al Smith, came unusually close for a Democrat. Senator La Follette was easily renominated and re-elected.

A New Governor: Philip La Follette

The progressives, charging that Kohler violated the corrupt practices act by excessive use of money in the primary campaign, put out anti-gangsterism. In a trial at Sheboygan the governor was acquitted.

The disorganized progressives played their ace card in 1930, the youngest La Follette, Philip. The stalwarts scoffed at his youth, but Philip went “to the people,” even as his father had done. Few communists ties in the state did not receive a visit from him and his rattling Ford car. “The chicken in every pot” had not materialized; the stock market had crashed and the depression was well on its way. The La Follette slate won everything. La Follette and Charles Hamerlsley, the Democrat, had no difficulty in winning over Charles Hammersley. Demographic progressive power that still retains its identity. The activities of the disenfranchised, Gov. La Follette put over a strict utilities regulation act, an unemployment insurance act, and, in a special session, obtained a big appropriation for unemployment relief. Part of these funds were used to build the railroad overpasses that were ridiculed as “roller coasters” in the following campaign.

The La Follette cure for the depression was no more effective than the Kohler kind. Discontent was growing in the state. Kohler was again the stalwart candidate; a young editor from Ashland, John B. Chapple, who copied the La Follette methods of campaigning, was the stalwart choice to run against Senator Blaine, up for re-election.

Kohler scored La Follette expenditures and won with about the same margin that he had been defeated two years before. Chapple, speaking mostly against radicalism and atheism at the University of Wisconsin, sprang one of the greatest upsets in Wisconsin political history and topped Blaine. Blaine, the fire-eating campaigner, had played the dignified part at the La Follettes’ suggestion, and had completely ignored Chapple. To this his followers attributed his defeat.

The discontent was not yet satisfied. Chapple openly backed President Herbert Hoover in his campaign for re-election; Kohler let himself be identified with Hoover. Franklin Roosevelt’s new deal was dawning. A sickly nation, weary of inactivity and lack of leadership in the White House, decided to vote out Hooverism and all that was a part of it. Wisconsin felt with the nation. Going Democratic for the first time in more than 40 years, it elected F. Ryan Duffy senator over Chapple and A.G. Schmedeman governor over Kohler.

The Progressive faction had always depended on the votes of Democrats. Now, for the first time since the senior La Follette started his faction, the Democrats were again in power. They had leaders, they organized in towns and counties, in villages and cities. It would seem that it was this revival of the Democratic party, plus the growing agrarian discontent with the existing parties, that brought the death of the Progressive faction. The history of the Progressive faction should by rights trace the memorable careers of its senators and congressmen in Washington. They formed the nucleus and the motive power of a national progressive movement that still retains its identity. The activities of the senior La Follette, particularly, are inscribed forever in American history. But this is a record of the faction in the state, and that story has now been told.